By Gina Castro

Adorned with an elegant hat and a head held high, African-American women are known to sport their crowns each Sunday. Wearing a hat, also called a “crown,” to church on Sunday is a cherished tradition within the African-American community. This tradition can be traced back to Africa. In Africa, hair is symbolic. It symbolized one’s family background, social status, spirituality and tribe. Decorating the head and hair was an essential part of the dress, especially in West Africa, where most black people in America have their origins. Women, depending on their tribe, would embellish their hair with braids, silver coins, cowrie shells and beads.

When Africans were sold into slavery and brought to the Americas, many of the African women continued to style their hair. This became problematic for slave owners because they were afraid white men would be attracted to these women, so colonizers enacted laws to limit the Africans’ cultural expression. Esteban Rodriguez Miro, the Spanish governor of Louisiana, created the Tigon Laws of 1786, which forced women of color to cover their hair. This law was made to mark these women as inferior.

However, black women found a way to turn the tables by making the head wrap fashionable. They used unique colors and wrapping styles to enhance their skin tones and facial features. Hair wraps are still popular today. Although not all African women had access to stylish fabrics during slavery, this loophole helped pave the way for African-American women to take pride in their hair, head wraps and, eventually, hats.

By the Reconstruction Era, African Americans gained more rights and opportunities, which allowed them to express themselves more freely. Somewhat a combination of rebellion and a revere for church, African Americans chose to dress their absolute best from head to toe each Sunday.

“I think for black people, especially if you were working in the cotton fields all day, you never got a chance to look good. You certainly don’t look good in the cotton fields,” Mamie Hixon, English professor at the University of West Florida, said. “Sharecroppers had on a sack dress, a sack on their back and a rag on their head. So, you have a cause when you go into a house of worship to put on a nice dress and a crown— the crown you deserve.”

Today, most women follow this tradition simply because the women before them did. Lola Presley, charter member of the National Coalition of 100 Black Women Pensacola Chapter (NC100BW), recalled that every woman in her family carried on the tradition.

“My mother was born in the 20s. She always dressed up with a hat on Sunday. My mother, grandmother, aunts and cousins, they are all from that era. They all wore hats,” Presley said. “It was a tradition on the day that you get dressed up, you went to church and you had a hat on, so when it got to my generation, of course, I did the same thing. I love hats. I passed them along to my daughter.”

Member of the National Council of Negro Women, Julia Arnold, 89, went to a Baptist church and a Lutheran church growing up. She remembers noticing a difference in how people dressed at each church.

“Hats aren’t in Lutheran churches as much as they are in a Baptist church,” Arnold said. “I guess it’s because the Lutheran church is more German oriented. I wore hats when I went to the Lutheran church also, but they didn’t wear hats like those Baptist folks do.”

Dr. Natalie Hardeman, First Lady of Antioch First Missionary Baptist Church, remembers the planning and detail her mom, a first lady, too, did before each Sunday.

“As most were getting ready on Sunday morning, she was already ready for church by Saturday. Every outfit that she wore to church, she had a hat to match it. Every single one,” Hardeman said. “She has never gone to church without a hat on.”

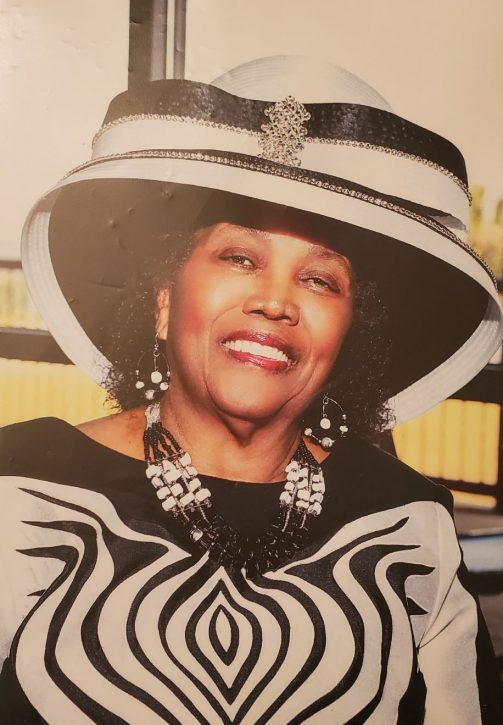

Pairing an elegant skirt suit with an equally classy hat empowered black women. It made them feel “seen,” as Presley described. “Wearing a hat says you’re sophisticated, trendy and classy. You’re going to be seen if you’re in a nice hat,” Presley explained. These hats are more than a basic head covering. The hat is an extension of black women’s original crown: their hair.

“Black women, traditionally, in black culture your hair is your pride and glory– your crown. So, the hat became a kind of crown, and it denotes regalness as well,” Hixon said.

Black women’s hair has been scrutinized since the dawn of slavery. It’s been stereotyped as “distracting,” “unkempt” and “unprofessional.” These women still experience hair discrimination today. In 2019, Dove found that black women were 50 percent more likely to be sent home from the workplace because of their hair. Just this year, California became the first state to enact a law prohibiting the discrimination of natural hair. That law was coined the Crown Act.

Each year, NC100BW hosts a heavily attended hat show to empower women. This year would have been NC100BW’s 19th Annual Scholarship and Hat Show. It was cancelled due to COVID-19. Hixon, who was charter member president when NC100BW’s Pensacola Chapter was established, created the idea for the show one year when the organization’s plan for the annual fashion show fell through.

“One part of the coalition’s national mission statements is to empower women at various stages in their lives,” Hixon said. “About the time of the meeting, I had just finished reading this book called Crowns. So, I asked ‘Why don’t we do a hat show?’”

Inspired by Crowns, a book featuring portraits of black women in Sunday church hats, Hixon launched what would be the first of many hat shows. The Pensacola Chapter loved the idea. Women from all over Pensacola and neighboring cities came to show off their crowns. The hat show has multiple categories, including the hat with the most hattitude, the largest hat and the fanciest hat. Hixon also thought to use ticket sales to fund scholarships, which were awarded to students of all genders.

“Women worked hard and that’s how we knew that this show was going to be a hit and stayed a hit for several years,” Hixon said. “Women looked forward to designing a hat or buying a hat from a local shop. We always did that show on a Sunday at two o’clock, so women just came after church since many of them were in hats anyway.”

The hattitude category is the most popular. When Coming of Age asked these women if they have hattitude, we were met with a resounding “Yes.” But what is “hattitude”?

“It’s a hat wearing attitude,” Hixon explained. “Not only are you wearing the hat with a certain kind of demeanor and personality, but the hat itself speaks. It has a personality. That’s hattitude.”

Although hat wearing is a beloved tradition, all traditions are bound to change. Each generation adds their own personal touch. Arnold explained that almost every time she leaves the house now it’s with a hat on. Pensacola historian, Teníadé Broughton has practically trademarked headwraps in Pensacola. She is hardly ever seen without a beautiful fabric framing her face.

Dr. Hardeman explained that she is one of the few first ladies in the area who continues to wear a hat on Sundays, but even she doesn’t wear a hat each Sunday like her mother did when she was a first lady.

“A lot of people have gotten into wearing fascinators, instead. A lot of ladies in the traditional churches have gotten out of wearing hats. There are still some that do. But as far as an every Sunday thing, we hardly wear them. We hardly wear them because they’re heavy and uncomfortable,” Dr. Hardeman explained. “It’s more comfortable to wear a fascinator. Some pastor’s wives don’t even wear hats. They just wear dresses or pants when they have to dress up. As the times change, traditions change.”

Even if hats transition to fascinators or if hats somehow phase out, there is one thing for certain: a black woman’s crown is always in style.