By John Baradell

Interviewing Anne Waldman is likely daunting for any writer. Waldman is one of the living legends of literature, a major American poet, an intellectual of the arts and communications, a committed feminist and activist, a spiritualist, and an inspiration for all. She has magically combined her extraordinary talents into musically-inclined performance art for decades.

Since the 1960s, she has been a member of the Outrider experimental poetry community and also has been connected to the Beat poets. In 1974, along with Allen Ginsberg and others, Waldman founded the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at the Naropa Institute (now Naropa University) in Boulder, CO, where she is Distinguished Professor of Poetics and director of Naropa’s Summer Writing Program.

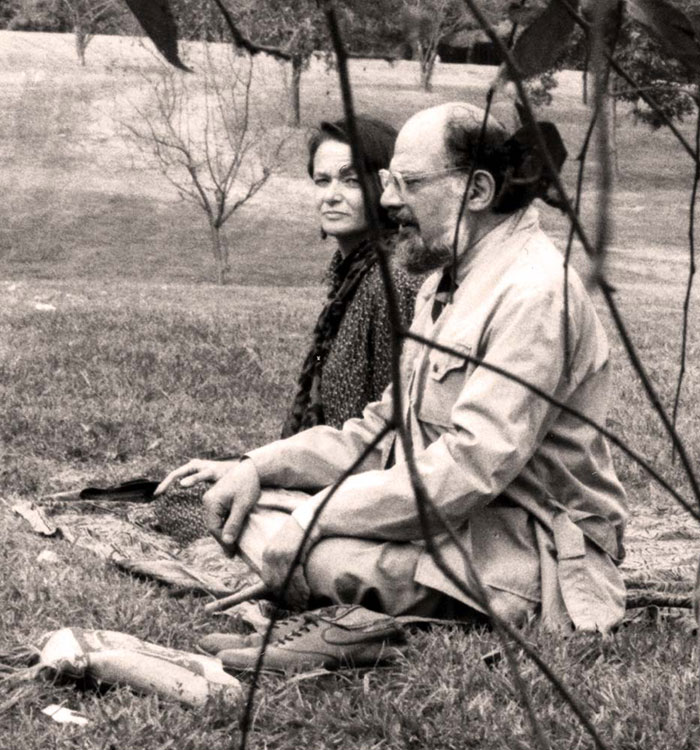

Waldman has been a vocal proponent for feminist, environmental and human rights causes for more than four decades. She became a student of Buddhism in the 1960s. Ginsberg once called her his “spiritual wife.” She is married to writer and video/film director Ed Bowes.

“Waldman’s work is the antithesis of stasis. She is a flame,” one reviewer noted.

Waldman answered our questions during a recent blizzard in New York City. Pensacola State College and West Florida Literary Federation are elated to be cosponsoring her workshop and performance from April 21-22 for Pensacola State’s Lyceum Series.

Your work is characterized by bold, honest communication. What’s the best way to relay the importance of that perspective of art to those who are influenced by the digital world?

I think that poetry has a long enough history and track record to count as a major stream of artistic possibility. There are still would-be poets who are hungry for the good news of poetry and might be fascinated by new forms and genres that are in sync with the changing modes of communication. I am not sure that book reading will totally disappear—and there’s the huge range of spoken word and performance with the collaboration of video and music. There is so much poetry activity online as it is. I think giving an exciting overview of some of the most exciting periods for literature, to show documents and videos, would be a way to get people to see the energy and excitement of the naked word! There are some terrific anthologies round including the “Resist Much/Obey Ltttle” tome. Poetry is a site of strong activism these days. I am curating a festival in Mexico City this spring, and people might want to also check out the Jack Kerouac School Summer Writing Program in Boulder at Naropa University, June 11-July 2, to get really charged. I see the digital world as a “skillful means” for poetry.

Some writers refer to you as a one of the original beat poets, but you have been quoted as being more a “second-generation beat poet.” Your voice is also part of the “outrider” community. What is your opinion of labels that are placed on art?

Well, I’m a generation under William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac were all senior to me. I was newborn when the Beat Generation started. Labels can be handy to locate and place and describe the histories of artistic communities. “Outrider” means being outside the academic mainstreams of poetry yet not “outside” the worlds of poetry. You ride parallel. It’s a term that was used in herding sheep, I believe. I don’t see these terms as being placed “on art;” rather, they are useful markers. Beat comes from the word “beatitude” and from street slang: “I’m so beat!” These sources are interesting to me. But it’s advisable to be wary of labels. Go to the work itself and expand your own understanding and view.

Your literary work is overtly musical in nature. What is your viewpoint on music’s effect on the literary arts, and on art in general?

It’s wonderfully inherent in poetry. Melopoeia refers to the sound in poetry, akin to music. Poetry was originally recited to a lyre. Music is a wonder of the world and there are so many forms and expressions of it—it’s overwhelming! I enjoy working with all kinds of music. Right now, I’m working with classically trained composer David T. Little, on an opera. I work with my son, Ambrose, who plays piano and creates soundscapes for poetry My nephew, Devin, is a sax player. I also work with Thurston Moore’s guitar and Meredith Monk’s vocalizations…endless possibilities. I want to find an oud player to work with next.

Allen Ginsberg famously called you his “spiritual wife.” Your work is influenced by a deep understanding of his formidable talents. How is that demonstrated today?

I think we shared a view in our understanding of Buddhist philosophy. Something about having to build one’s work and life on a sense of compassion and a broken heart. That commonality of broken hearts would generate more understanding and sympathy among people. Allen was extremely generous. As he was dying he called all his friends and asked what they needed. Could he send money? That sort of thing.

We founded a poetry school together at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado. His work is quite available, and there are new books all the time. Most recently, just out in April, is his “The Best Minds of the Beat Generation: A Literary History of the Beats” from Grove Press. I wrote the foreword for it. It’s a great eyewitness account from Professor Ginsberg. We have a Ginsberg scholarship at Naropa. I think his legacy continues. The Beats were a cultural intervention, not just a literary intervention.

For generations, you have been “the girl” in a male-dominated society. Any thoughts?

Well, there are others, Diane di Prima and Joanne Kyger principally; both are fine experimental poets who were also key to the vision of Naropa poetics. There are others that you can read about in some anthologies that focus on women associated with the Beat literary community. I had the privilege early on of getting to know Allen very well; he was like family. He knew my parents, we worked together at Naropa for many years, and we traveled abroad giving readings. We were close, too, in New York.

We spent three months at a Buddhist seminary in Canada to get understanding and that is very bonding—meditating all day in the same environment, snow falling outside the window in Lake Louise. Burroughs, as well. was a regular teacher at Naropa. In the beginning I was a bit intimidated, and it was harder for women even in the 60s/70s era … and the Beat track record was not so good, and though I didn’t appreciate the misogyny in some of the writing, there was something touching about the camaraderie of the guys, a tenderness. And I never felt any condescension from them.

William has a dream where I am “Mother Naropa” and I seem to be taking care of everyone, so that’s friendly. I respected and was familiar with the writing of these giants, which included Gary Snyder and Philip Whalen and Gregory Corso as well, and Amiri Baraka, who has a Beat phase, and Kerouac of course, which helped.

I felt the importance of their cultural intervention in the USA and around the world. The politics, the influence of jazz, the importance and debt to black culture, and the attention to ecology and Buddhism and candor of imagination all continue to be relevant in the legacy. There are so many empowered and extraordinary women writing and publishing and changing the frequency now, so things do evolve—I love that. I have a strong link to the New York School, and felt the encouragement of Kenneth Koch early on, as well as the support from Barbara Guest and Ted Berrigan.

How has your son’s extraordinary talent and overall mindset influenced you?

This has been one of the joys of my life, working with my son Ambrose Bye. We squabble as would be expected of any mother and son and he claims to “keep me honest.” He’s can be quite the Luddite anarchist, and when I think he’s getting too extreme he says, “But YOU raised me this way!” He did grow up at Naropa and he works at the recording studio there in the summer.

His father Reed Bye is a poet too, and Ambrose has helped produce some of his father’s songs. We have our Fast Speaking Music label with Devin Waldman, my nephew, as well, and an array of poets and other musicians have been involved with many projects. Ambrose has a good ear, and I really appreciate the complex dynamic soundscapes that he creates; they’re often quite startling and meditative. So, there’s respect, and I like the folks he works with, too. There’s a terrific new jazz poetry dynamic that is emerging.

Please tell us your spiritual message about life and the arts’ importance in it.

Art can help wake the world up to itself. We can’t live in a world that’s all business and war. We need art as nourishment in this crazy world, to be in touch with our imaginations, and to be elevated by our sense perceptions and the dance of language and beauty in poetry. To see into the future, as difficult as that may be. To stay open and alert and caring for others and to nourish children, as well. Children love art when they get a chance to play in it. It’s strange that we feel we have to struggle for art: it should be a given, with its spiritual power and imperative. Who would want a world without art? That’s a frightening pathology, and I worry about this. That would be a hell realm: a world bereft of its heart and mind.

Anne Waldman Workshop and Reading

New York poet, writer, social activist and international performer Anne Waldman will present a workshop and a combined reading and musical performance in April at Pensacola State College. The performance is titled “Makeup on Empty Space: Poetry in Performance.” PSC and the West Florida Literary Federation are co-sponsors.

Waldman’s son, Edwin Ambrose Bye, is a musician who partners with his mother for performances, including the one in Pensacola. Waldman’s workshop will be Friday, April 21, from 11 am to 1 pm at PSC Library, Building 20 Room 2051. The reading and musical performance will be Saturday, April 22, at 7:30 pm at PSC’s Ashmore Auditorium. The workshop is free and open to the public.

Tickets for the performance as follows: general admission, $11; reserved admission, $9; seniors (60-plus), PSC Alumni Association members, students and children, $7; PSC Seniors Club, PSC faculty and staff, and PSC students with proper ID, free.

For more information about the Pensacola event, visit wflf.org or facebook.com/annwaldmanpensacola. For more information about Anne Waldman, visit annewaldman.org.